After I posted my thoughts about literary fiction, I asked Adam to comment on them. After all, he was an English major and a quick look at our Goodreads profiles will confirm that: he reads far more literary fiction than I do. Two weekends ago, he commented and it turned into a discussion over Twitter. He certainly gave me a lot to think about. I'm open to mixing more Literary fiction into my reading.

Here's a lightly edited transcript of our conversation.

Adam:

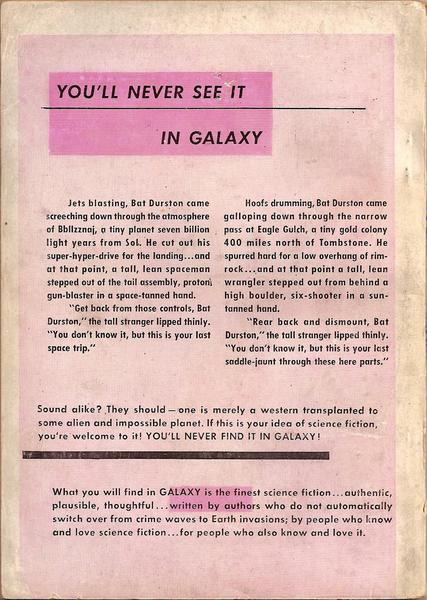

My proposal: literary fiction is most interested in us and our world, nonliterary fiction in escaping those things. Plus: skill. Skill is what earns you the capital "L" in "Literature" and a place on a professor's syllabus. My suggestion is essentially in line with academia, I think, but they are much more fundamentalist about it.

Joe:

Where would that put, say, mysteries or Grisham style stories? I'd put Agatha Christie or Grisham in our world. I took skill as a given. I've seen very skillful SF/F authors that still get ignored by the academy.

Adam:

They are SET in our world, but Christie and Grisham write escapist novels. Let us grant that this is so. To what purpose do they employ those skills? What are they interested in? People? Rarely. It just so happens I have a case study handy for my personal principle of literature handy...

I reserve my five-star Goodreads rating for Literature and recently gave it to Hyperbole & A Half, a humor collection. Now one might reckon - and as a rule - the highest that, say, a side-splitting humour collection might get from me is 4. You can accomplish your mission of making me laugh in the hardest possible way and I'll give your book a 4-star rating. But included in the book are, among others, her 2-part piece on her depression. Clinical, that is. So she writes this half-prose/half-comic (modeled after "rage art", tho' she's actually a great artist) achieving a very specific effect, and talking about something very serious - well - while making us laugh. It's very impressive. The entertainment value in that 2-part series doesn't take precedence over her discussion of how it feels to be depressed.

This is also why I see an interest in Literature as an expression of maturity, and a diet of 100% geekery as stunting. To enjoy (& learn to enjoy) Literature is to show interest in others, in your world, in thought - to find them entertaining. In a sense, it comes to the adage "The less you find interesting, the less interesting you are." In film, tentpole films are meant to capture the most viewers by appealing to what even the boring find interesting.

Reckon I'm done. Am I making sense?

Joe:

Yes. Not surprisingly, I don't 100% agree. I think. I'll probably be considering for a while. But you are making sense.

Interestingly enough, my taste in TV shows is beginning to run strongly towards the Literary and away from mass market. At least, what I'd consider literary. Mad Men & Breaking Bad strongly caught my interest. I surprised myself with how much I like Mad Men. It's odd too. I suspect that if I read Mad Men as a book, I wouldn't like it. As TV, I love it.

One area where I disagree: I think hard SF can really open the mind to potentials yet unrealized and encourage optimism. I see many people who's focus is on our world who get obsessed with the negative in our world. True, it's there. But it doesn't have to be there forever. There are vistas over the horizon just waiting to be seen. I think people who are unable or unwilling to see those vistas, are very boring people indeed.

I see an interest in SF as an expression of maturity as well and a diet of 100% Literature as equally stunting. I think there needs to be a balance, which is why I disagree with elevating Literature to the top ranks and consigning everything else to a lower plane.

There, now I'm done. :)

Adam:

Well, don't forget I enjoy SF, F, et al. I often use the metaphor of a "diet" b/c I'm not dogmatic. But what you describe is escapism. And also, notably less challenging for the reader than Literature. That suggests something, to me. (although to be fair I generally use difficulty as a signifier of the better course, which is not always true)

So a balance? Yes. Just like there should be a balance between rest and study. And both have their benefits. But I think SFF fans like to pretend the former is the latter so they can avoid the latter altogether.

Your turn.

Ah, sorry, 1 more thing: I think the real world tends to look overwhelmingly dreary to people adrift in fantasy. No, I take that back. It's not what I meant. Badly said. And god, the world looks dreary to me often enough. When I think of a better way to say it I will.

Fin, for now.

Joe:

I'm going to accept your retraction but it did spark a half-though here. I sort-of agree with that statement. I think the real world offers both immense dreariness and reason for optimism. The Lit I read in college seemed more steeped in the dreariness side. So I tend to view Lit as overwhelmingly dreary. That it focuses on the dreary to build street cred and has a tendency to make the world look worse than it is. But maybe I'm just reading all of the wrong Lit books.

Back to the main thread. I could fairly easily rank some of my favorite authors along an escapism <-> reality scale. There's popcorn literature as much as there's popcorn film. More even, probably. I can definitely tell when I'm reading because I'm tired and I don't want to think and when I'm reading something that I know will make me think.

When I think of reality vs escapism, I think about the regulator pondering what regs to write. What's easier for him to envision? The world he lives and breathes daily, where everything must be spelled out in great detail, to prevent anyone from finding any loopholes for wrong doing? Or the world of tomorrow that might be and that his regulations of today might strangle stillborn and prevent from ever coming to be? For him, I think escapism is a necessary component of life.

If you can't imagine tomorrow, you can't make sure we're in a position to build tomorrow. I also think of all of the engineers who were inspired by 60's SF (written and visual) to invent what they did. Their inspiration, from their escapism, helped create the reality that today's Lit writers live in and write on. I think it would probably do some engineers good to read more Lit, to consider how their work might be used and abused. Contrariwise, it might do some Lit writers good to read some hard SF, to see not just how broken humanity loses themselves in tech now but to see why those who work on tech do so and to understand the what engineers gain from their escapism and how that drives them. I think taking SF seriously is a step towards understanding certain types of people better.

To, maybe, some up: I think what is rest and what is study may be in the position of the reader. For me SF is rest and Lit is study. Was is the same for Hitchens? Is it for Franzen? Or would understanding SF be study for them?

Over.

Adam:

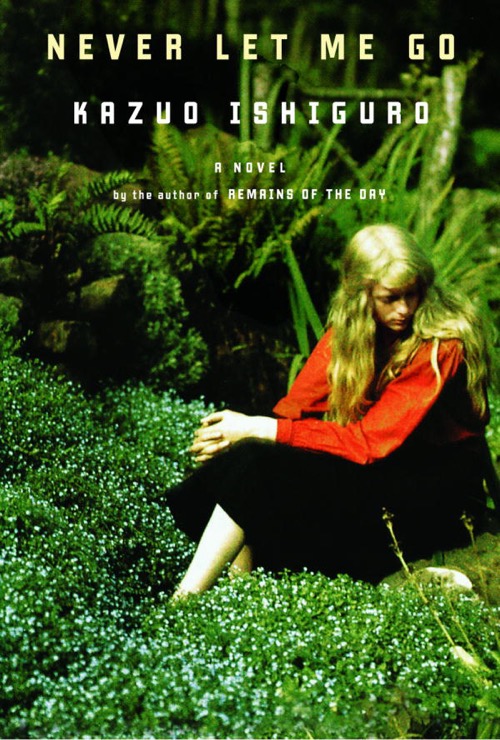

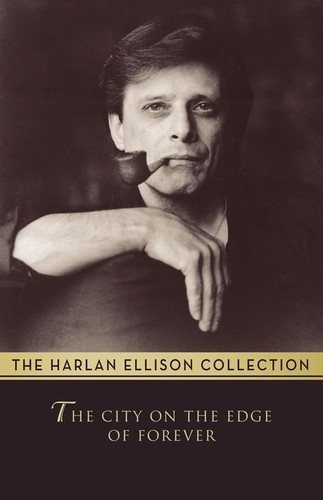

I just spent a moment trying to think of SF/F books I would consider Literature, since I don't believe, in theory, the title excludes them. Came up w/ 1984 and Atlas Shrugged. Also The Handmaid's Tale. Other contenders?

Joe:

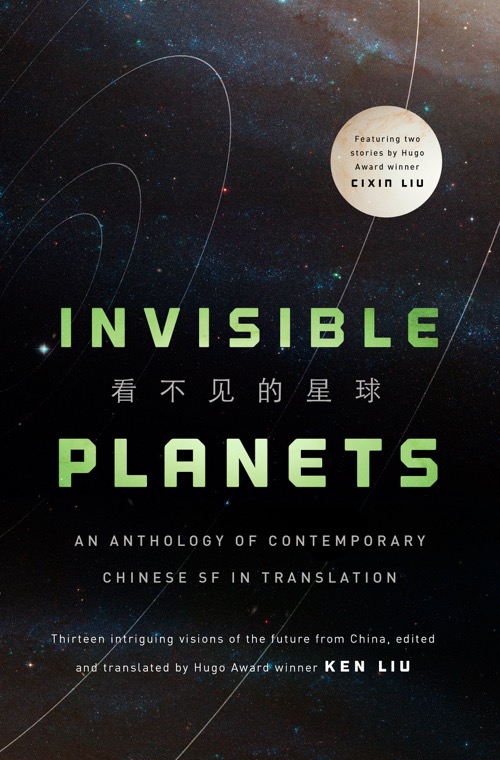

I haven't read all of these, but these are what I've heard. Some of them will probably end up on next year's reading goals. Gene Wolf's novels. Michael Chabon's Yiddish Policeman's Union. The Dispossessed, China Miéville's stuff. I'm less sure about that last one. But I've heard it could qualify.

Adam:

OK, I'll give you China Mieville's The City & The City, actually. In fact I gave that one 5 stars last year.

Joe:

See, I knew someone reputable had spoken approvingly of it. :)

Adam:

Chabon's The Adventures Of Kavalier & Clay actually won the Pulitzer. Ever check it out?

Joe:

No, but it looks like a definite candidate for next year's reading list.

Adam:

I don't think Yiddish counts for me. I mean, Yiddish is cute as hell and thoroughly entertaining, but it hasn't much ambition, really. Chabon's Telegraph Ave, now is a great thing. You would absolutely hate it, I think. Maybe I might make you read it after you lose this year's bet?

Joe:

Ha! I'm picking my bets more carefully this year. Wait 2 years for when my heart leads me to bet on Paul winning the Presidency.

Adam:

If Paul was the nominee I could conceivably see myself voting for him too. Without a hope in the world, likely, but I could.

Joe:

You've answered my unasked question though, on whether a story must be set in our world to be Lit. I would have said no and apparently you agree. A continuum between not of our world popcorn and character studies. Whereas "our world" stories can span the continuum from popcorn thrillers to character studies. Or, going back to my post, the difference between under the surface and above the surface plots. Your proposal was "interested in us and our world" vs "escaping those things". I'd argue for shortening it down to "interested in us", whether in our world or not.

Adam:

Thought of saying just "interested in us", but I dunno, didn't want to leave out something brilliant about environments, etc. Asimov's Foundation series, etc. always left me wondering if someone couldn't successfully write literature about a Thing. Say, the environment or a corporation. But without reducing them to themes.

I don't know, it's still a half-formed thought. The problem being that an inhuman Thing doesn't engage our empathy, which makes it damned hard to hook an audience. Anyway: was trying to be really inclusive and leave myself open to possibilities. But as a rule, sure: "interested in us".

Joe:

I can almost see it. Environment, yes. Corporations or nations would seem to boil down to the people who make them.

"Corporations are people, my friend".

Adam:

HA... OK. That's the first time I've laughed at someone using that damn line.

Joe:

I will say that I'm open to reading any Lit that isn't dreary. Or perhaps is only 50% dreary. I refuse to believe that it's impossible to write about humanity and only get dreariness out of it.

Adam:

I'd be willing to trade novel choices with you.