"Something I’ve been thinking lately," our dear webmaster Joe has recently written. "Am I different as a Christian than I would be if I wasn’t a Christian? Am I just wasting my life?"

Then he linked to a rap video appearing to strenously urge its viewers not to knock over convenience stores. DON'T WASTE YOUR LIFE, it demanded at its end via big white letters.

It probably goes without saying (but here it is anyway) that I've been worrying for Joe ever since. I had no idea he was knocking over convenience stores. And what's worse, I still don't know what's driven him to it. Does he need the money for crack?

Here's the worst of it: Separated as we are by just under 900 miles of amber waves of grain and purple mountains' majesty, I'm practically powerless to help the guy - except perhaps to wire him a little green, and wouldn't that just be enabling? My budget says yes, yes it would be, which means all I have left are my words.

And here they are, Joe - and on a public blog, no less, because the best antidote for darkness is the bright beam of posterity.

Joe, your dilemma highlights another problem with modern-day Christian theology: that is, what exactly a good Christian is supposed to do with his or her new life in Christ. Many (even most) Christians will of course scoff at the idea that this is any sort of quandary at all. "What does the Bible say?" they might respond. But my opinion stands that 'tis truly a tad tricky.

Here's why: the Christian New Testament of the Bible is an extremely apocalypse-focused collection of texts. Many scholars in fact agree that early followers of Jesus expected the end of the world to occur within their lifetimes or shortly thereafter, possibly because Jesus told them so (Matthew 24:34 - and no, He's not referring to the Transfiguration). Thus the overriding directive for Christians was to go forth and create new Christians, occupying yourself with as little else as possible - indeed, relinquishing the gift of marriage unless you just couldn't resist your sexual urges, and living as if you weren't married if you were.*

(*And as an aside, boy has that advice from our dear apostle Paul resulted in headaches for young Christians since; many are the Bible-believing boys and girls who have had to struggle with the idea that they're settling for serving their beloved God less by exchanging vows. Would that Paul had never written the stupid part - if he actually did. Anyway:)

If you desire to compare your accomplishments to that original standard, Joe, simply ask yourself how many people you've recruited for the Christ, and deduct points for all the time you've spent married when you could've been SAVING SOMEONE FROM ETERNAL TORMENT IN THE SNAKE PITS OF HELL.

Ahem.

There are other yardsticks available with which to measure your faithfulness, though, since as you are probably aware we are now well past those early, heady days, and we must now take note that God's Holy Church has been caught somewhat flat-footed by just how big a procrastinator its saviour has turned out to be. Pastors and priests usually explain our unexpectedly long wait for Jesus' second coming as an act of mercy on the part of the Lord; they say He is pushing back the final hour to allow more chances for salvation. Knowing that God's love is infinite and that He has now shown the sinners of this world so much love that they have waited well over a thousand years longer for His return than they waited for His arrival in the first place (the first references to a messiah at best occur in the Book of Isaiah, written in the 700's B.C.), the Church and we members of it should probably figure out how we're supposed to pass the time.

We will toss Paul's suggestions into the recycle bin, then (because Lord knows, someone will dredge them up again), and consider other Biblical advice. The Teacher of the Book of Ecclesiastes has some, though readers disagree as to precisely what that advice is; Christians and Talmud-lovers suggest Qohelet pushes for his readers to keep their treasure in Heaven, as Jesus would say, while people who actually read the book understand him to be basically proferring the same advice as Voltaire's Candide: "tend your garden", i.e. enjoy your work, wife, and life - in short, function as you were made to function - and leave the rest up to God.

I find it an attractive suggestion, Joe. What say you?

I should warn you, modern Christian thought rather rejects the Qohelet Theory. Rather, the view of today's mainline Protestant congregations is that your lifespan here 'pon Earth is a self-improvement project. You are meant over the course of your days to be slowly but surely perfected, to morph from a vile, despicable convenience store robber into a poor copy of Jesus Christ. The climax to this evolutionary narrative is your death, whereupon you are to complete your transformation (no matter what your spiritual state at the time of your deceasing) into a glorious new creature.

This option is also attractive, actually, but in my experience deceptively so; self-improvement is hard, stressful work if you take it seriously. Martin Luther addressed the difficulties in a treatise on Galatians. To paraphrase him, if you try to become a good man and think you are succeeding, you are a deluded egomaniac - and if you try to become a good man and fail, you will beat yourself up about it, since Mankind cannot be good enough.

Unfortunately, Luther's solution for this problem - "passive-righteousness" - is one of those ideas that sounds great on paper because it makes use of theology, but doesn't make any sense when you actually try to apply it. He claims that we must simply cease to struggle to be good (presumably "active-righteousness") and allow the Holy Spirit to do the work for us.

One only has to ask, "What does this mean I should do?" to realize it's hogwash. By and large, good things happen when we do them; nothing happens when nobody moves. Mankind's effort is clearly involved, So it clearly doesn't pass the real-world test (and is also horrifically debilitating) to declare nobody can be "good" via their own devices. Yes, you can argue that the results will never equal the amazing goodness of an omnipotent, omniscient person, the every action of whom is the standard by which Goodness is judged even if we don't understand how it could possibly be good at all - but what in the world kind of standard is that? A standard which you cannot reach, as I've learned since meeting my mother-in-law, is really no standard at all (and on the opposite side of the coin, any standard which you will reach no matter what is not exactly worth striving for either).

I would therefore say that the modern Christian concept of Life's purpose is usable, but the theology that accompanies it is not. Clearer some people are better than others and you should strive to be one of them. By all means, consider the question of whether you are a better person than you were five years ago and rate yourself appropriately, if you like.

But I'm personally still not quite crazy about it. To quote one of Franklin Deleanor Roosevelt's cabinet members (I forget which), "In the long run, we are all dead." Self-improvement is not a value in and of itself; taken alone, it is but vanity. Reward for self-improvement is only found in its context. Does being a better man, for instance, result in your being a better husband and father, thus benefiting the people you love? Is that a goal of yours? If yes, it is good.

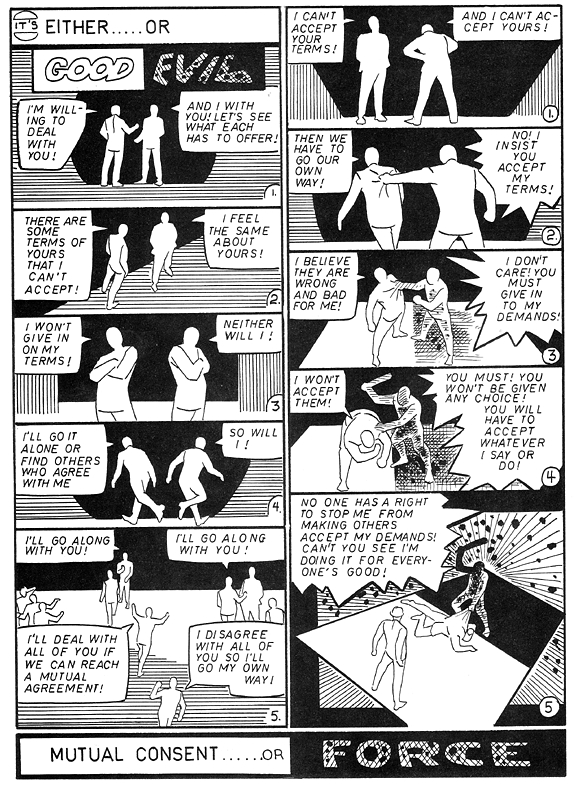

I'd argue instead for a result-focused lifestyle (and yes, "self-improvement" can be a result - but as I said, it's of no real use as the ultimate one), in which we strive to create the reality we desire.

Note that I am not suggesting a result-oriented life; there is a difference. A man who sets out to be a good husband and father has a chance of dying satisfied only if he keeps proper perspective about how much control he has over such matters.

We have actually come full-circle, since a result-focused lifestyle is exactly what the apostle Paul was suggesting nearly two thousand years ago, the important difference being of course that he had already taken the liberty of choosing the result on which to focus. When I first met my fiance, I was surprised to find her very skeptical about that focus; unlike me, she'd never thought of the commission as binding upon her. Nowadays I agree, if only because so many of my ideas about Christianity are currently in flux that I don't feel I have enough answers to share with others.

But I digress! Let me know which of these options you choose, Joe, or if you'll be selecting another. In the meantime, remember to adequately scope out your targets before you strike, and pay your taxes on whatever your take is.